A broader way to frame the M&V task

1.2. A broader way to frame the M&V task#

The SENSEI methodology for M&V defines the M&V goal as one of devising and applying a mapping from states and conditions after an energy efficiency intervention to states and conditions before it. The impact of the intervention is the difference in energy consumption between matching states and conditions. To this end, the proposed methodology makes a distinction between mapping variables and impact variables:

Mapping variables are defined as the observed and/or unobserved variables that must be similar between the pre- and the post-event periods so that a counterfactual estimation would make sense. In other words, mapping variables help us map from states and conditions after the event/intervention to states and conditions before it. The weather, the building’s occupancy schedule and the intensity of the occupancy (i.e. number of people or level of plug loads that correspond to full occupancy) are examples of mapping variables. As a general rule, an M&V model must be able to adapt to changes in the mapping variables.

Impact variables are defined as the unobserved variables that directly affect the impact of the energy efficiency intervention. The U-value of the building’s envelope, as well as the efficiency and/or the control strategy of the HVAC system are examples of impact variables.

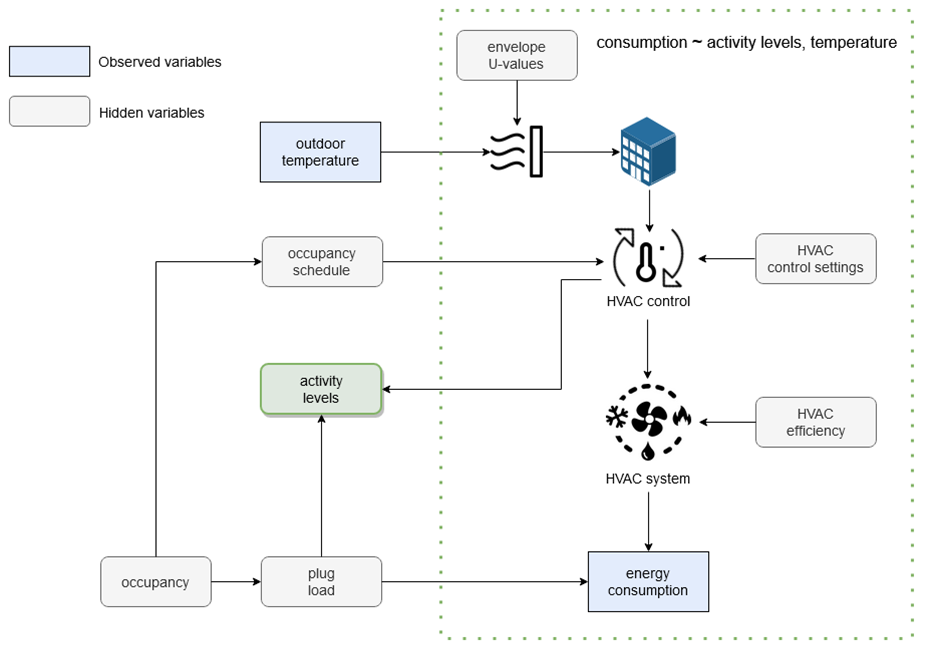

The interrelation between mapping and impact variables can be summarized using the simplified building model in the following diagram:

There are two (2) observations to be made from the diagram above:

We can imagine a hidden mapping variable called

activity levelsthat reflects occupancy levels and occupancy schedules indirectly: through the variability of consumption under similar external conditions (defined by occupancy-independent variables, for instance, similar outdoor temperatures).The impact variables affect the energy consumption given the activity levels and the external conditions.

The main idea behind the SENSEI M&V methodology is that we can have a valid, counterfactual prediction model by comparing the energy consumption before and after an intervention for similar activity levels and similar values of occupancy-independent variables (such as the outdoor temperature).

The general rules of the methodology are that:

For events that affect impact variables (such as an energy retrofit): First, pre-event activity levels are estimated. Then, a consumption predictive model is trained on pre-event activity levels and occupancy-independent variables. Finally, post-event activity levels are estimated, and the predictive model is used to create counterfactual predictions given the post-event activity levels and occupancy-independent variables.

For events that affect mapping variables (such as the maximum number of people in the building): A pre-event consumption predictive model is used to estimate post-event activity levels. This is done by finding the activity levels that force the output of the model to match the currently observed energy consumption. Note that if only mapping variables have changed, the consumption model is still accurate when predicting energy consumption. Then, the pre-event consumption predictive model is used to create counterfactual predictions given the post-event activity levels and occupancy-independent variables.

Events that affect both impact and mapping variables at the same time - for instance, upgrading the HVAC system and reducing the maximum number of people in the building (when plug loads are directly proportional to that number) - can be very problematic no matter how smart an M&V methodology is. Unless sub-metering or other additional sources of information are available, these events imply bad design and/or execusion of the M&V plan.

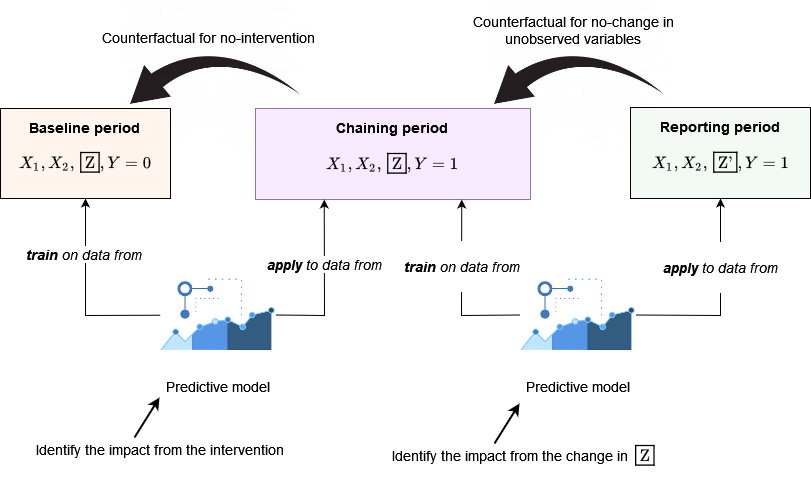

The idea of revising an M&V model as data from the post-intervention period accumulates already exists in the chaining method for non-routine adjustments proposed by the International Performance Measurement and Verification Protocol (IPMPV) application guide on non-routine events and adjustments (EVO 10400-1:2020). In particular, chaining requires the ability to monitor energy consumption after the energy efficiency intervention so that to infer potential changes in the unobserved variables. If changes are detected, a new predictive model is deployed with the goal of quantifying the impact of these changes. The counterfactual consumption during the reporting period is estimated as the impact of the intervention corrected for the impact of the change in the unobserved variables.

The chaining method is summarised in the next diagram:

The chaining method is meant to run when an event that alters the characteristics of the building’s energy consumption is known or detected. If we consider that an energy efficiency intervention is a known event that alters the characteristics of the building’s energy consumption, we could imagine an M&V approach that corrects/updates the M&V model as soon as we get enough data from the post-intervention period. This is the approach that the SENSEI methodology adopts for M&V:

A unified chaining method that adapts the M&V model after any known or detected event, including the event of the energy retrofit itself.

The subsequent chapters explain the M&V methodology in detail using examples of real datasets of building energy consumption.